When I was younger, musical genre seemed like fixed, if not predetermined, sets of musical audible or practical traits. Rock was rock because it sounded/looked/felt like rock, and jazz was jazz, etc. In time, however, it became difficult to establish any ultimate value judgment between these collections of genre-traits, and I became sceptical of the significance of what seemed merely to be consumer choices. This shift in thinking coincided with the emergence of clothing stores that sold ‘alternative’ fashions (remember Gadzooks?) to grab those consumers who had gone over to buying clothes from second-hand stores. ‘Alternative music’ was the same. Maybe at some point there was some true alternative, but by the time I was in high school it had become an empty, stylistic expression, even if I thought otherwise at the time. Same labels, same industry, same consumerism as the Madonnas, Princes, Michael Jacksons, and Garth Brookes of the world. Punk, which had also in the 70s been in part about interrogating consumerism, became by the 90s essentially about where you chose to shop. So while in States at least the charity shop or army surplus look was based on a rejection of Gap, JCrew, etc, during the 90s the neutral style, and not the essential rejection on which it was based, was co-opted and sold to the witlessly stylish consumer. So, what I’m saying is that genre (music, fashion, or otherwise), even when it has its roots in the most significant cultural rejections or social movements of our history, does not contain within it those original significances. I have now, finally, identified this perspective as being a large part of why I have never been comfortable with the question, ‘what kind of music do you play?’ As far as I’m concerned, it’s just not that important.

I’ve never been a classical composer, a punk, a southern rocker, a metal head, an electronic musician, an avant gardist, a folkie, a tradster, a country musician, a jazzer, or… you name it. I have never identified myself as any of these, although I’m aware that others have placed me in whatever category is most useful in whatever context. Many of these, though, have had something to do with what I do when I engage in musical creative practice. I don’t judge the impulse of people who settle down and cosy up to ‘their thing’ for decades of their lives – that seems to be how many people work, and subsequently is a much wiser career approach for an academic – but I can never, won’t ever, go far enough in any of these directions to the point where I am comfortable with a straightforward answer to, ‘what kind of music do you play?’. The answer is TLDR, i.e., this morning I worked on some recorded material in Max/MSP for a choral/electric Anglican Evensong, then played through a student’s jazz composition on the piano, then sang the through NOFX’s song, “The Longest Line”, in a country-fied style, because it is after all kind of a country song anyway, before examining a rock guitarist’s audition video. I started playing old timey music with some folks at work, and the guy who organised it seemed genuinely surprised that bluegrassy trad Americana music was firmly within one of my portfolio of musico-stylistic inclinations. It went something like, me: “yeah folks seem to not know that I have done all kinds of stuff that’s not, you know…”, him finishing my sentence: “avant garde type new classical music stuff”, me: “uhh, yeah…”, him, “yeah, that was me who thought that”.

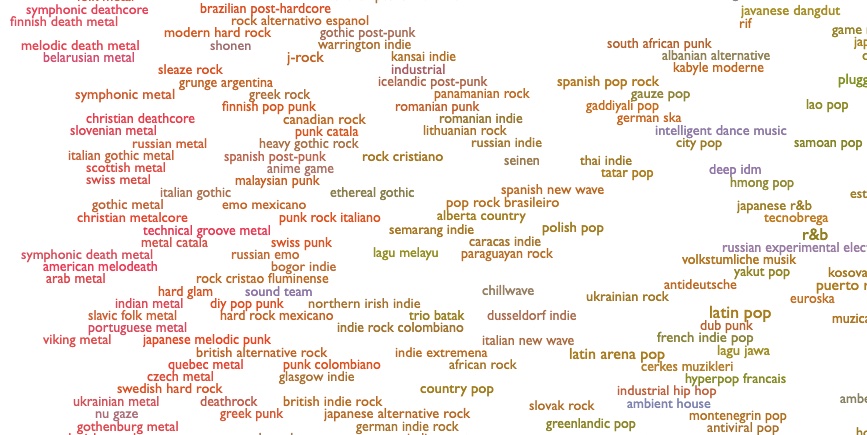

That shift in intellectual perspective has been toward seeing musical style and genre rather as an emergent quality of a broader complexity, like culture, i.e., what we people get up to when we’re responding to one another, socially, and to the environment. Here’s the point of this writing: I have little trust in any attempt to equate genre with broader ethical, moral or qualitative frameworks, and even less for the policing of genre authenticity, although I think practical authenticity, being authentic to yourself and your environment, is what it’s all about.

It's not that I am saying I don’t want to hear specific styles done well, it’s more that I’m saying I have no problem at all with tinkering with them, distorting them, even destroying them through practice. This is in fact what has always happened, and if it didn’t happen, we wouldn’t have differing musical styles, any more than we would have, well, languages and cultures. In the numerous performance exams I convened during my decade working for a conservatoire, I was often faced with colleagues who got very hung up on authenticity. Should Chopin be played like that? (Why should we care?) What about the composer’s intentions? (Is that really what they should be doing? How can I presume to know their intentions?) Is that real jazz, though? (If we determine that it isn’t ‘real jazz’, what then? Is it not allowed?) I think about the distance between institutionalised expressions of jazz (for example) and that early decade of jazz in New Orleans, when everyone was just doing what was natural in those circumstances, and how then music of such extraordinary consequence emerged, and how now, well, even with all those tens of thousands of hours of practice, very little of any consequence outside today's conservatoires emerges. Life is elsewhere. Again, it’s not that I don’t think preservation should exist, I just wonder where the 1910 New Orleans is now, and what people are doing, or for that matter, CBGB’s in ’75, Minton’s in ’47, or Florence in the 16th century. And I’m not too bothered by labels.

Many of my students will know I’ve little time for Wynton Marsalis’ publicly held position on “What Jazz Is-and Isn’t”. https://wyntonmarsalis.org/news/entry/music-what-jazz-is-and-isnt It isn’t so much that it’s technically incorrect: words, for them to work, must have meaning. But it is about the word, semantic, and not a very interesting ethical position. The style, or audible sonic and observable practical traits of the music, are beside the point, and as I said from the start, these traits do not contain their original significance. The point is that real humans made beauty out of their everyday lives and drawing strict lines around their creations dishonours the authentic conditions in which they emerged. This position does not represent “openness to everything” and “contempt for the basic values of music and of our society”. The contrary is true. A desire for genuine authentic responses to one’s social and physical environment is precisely the opposite of such contempt, and in no way suggests an openness to everything.

The bottom line is this. People make music socially and in response to their present circumstances. A more useful deployment of the concept of authenticity has to do with honest, ethical responses to these circumstances. I think we must really question the motivations behind the policing of authentic style. What does it say that we’re more concerned with polishing our relics than with building a new world? The Situationist Raoul Van wrote at the end of the first chapter of The Revolution of Everyday Life, the following statement.

People who talk about revolution and class struggle without referring explicitly to everyday life, without understanding what is subversive about love and what is positive in the refusal of constraints, such people have corpses in their mouths.

It may seem a kind of leap to go from my thoughts about style, genre and authenticity to thoughts about revolution and class struggle, but this is precisely what I’m talking about. Without the underpinning human story behind the music, style and genre are lifeless corpses, empty husks, no different than Coke vs Pepsi. Surface preferences. But these are often held aloft in institutions across the world as models for what our next generations of musicians ought to be doing without even pausing to think what it must be like to be a youth in today’s world. My proposal is that we let them tell us what they ought to be doing, and stop patrolling the boundaries set around established practices. But the people with corpses in their mouths want to keep the gates, police the boundaries, create the constraints, makes sure that the ‘in’ stay in and the ‘out’ stay out. They of course won’t be successful – they’ve never been – but they will waste a lot of effort on things that are ultimately meaningless.